In Defense of Vanity

Before we can be body positive, we have to recenter who we're beautiful for

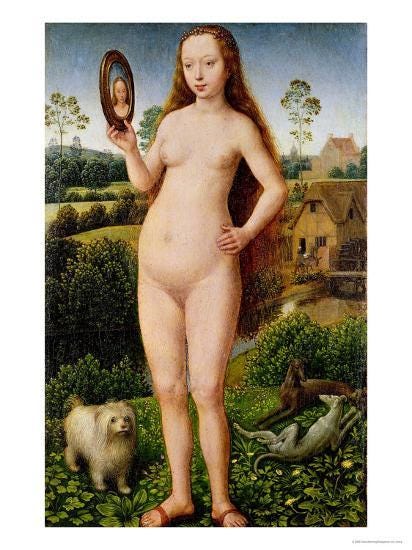

You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.

The real function of the mirror was otherwise. It was to make the woman connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight.

—John Berger, Ways of Seeing1

For two years in my life, 17-19, I was a professional model. Technically. I never made a cent, and living, as I did, in north-central Florida, and not New York or Los Angeles or even Miami (three cities that the agency that represented me existed in), I was only ever even eligible to try to book jobs when I had time off from school to leave and go to those markets. Really, beyond a few stories, and a few years with short hair, all “being a model” ever did was to certify that I was beautiful, to make it official to people outside of me.

We frequently look to consensus or expert opinion to determine these things. What is beautiful. Critics tell us that art is quality, fashion writers determine if a trend will persist or die. Growing up as a tall, slender person in the West, and as part of a family of really gorgeous people, that I was beautiful was as clear to me as that my eyes are hazel, or that kiwis make my mouth itch. While I still know myself as beautiful, and have always held to this, I was not considered beautiful—or perhaps attractive—by my peers from about ages 12-18. Yet, I never wavered in my conviction, even during a few awkward years when perhaps I should have.

I am not complaining. This is just a data point. After I was signed, there was some shift, an increase in my cache because people had to believe I was beautiful, too. I’d been signed with a pretty prestigious agency—FORD, and later Elite for international work that never came to fruition—but I was still not seen as attractive, datable. This is not the point, though. I mention the peer view, the years of being seen as unbeautiful, because you must understand how intense my family’s belief in the beauty of their children was, so intense that it shielded me from being hurt by how the people I went to school with perceived me. Most of all, this beauty was stressed by my paternal grandparents, who lived next door, and whom I saw nearly every day until I left for college. My parents rarely spoke of our, me and my brother’s, looks—but Clare, my grandmother, would frequently invite me to visit friends or help her put on a tea party with the line “they’ll so love to see your beautiful face.” My youth, my beauty (perhaps the same thing in those instances) was like the larkspur or wild plum that she placed in airy arrangements on the table and sideboard: a pleasant adornment, a relief for the eyes.

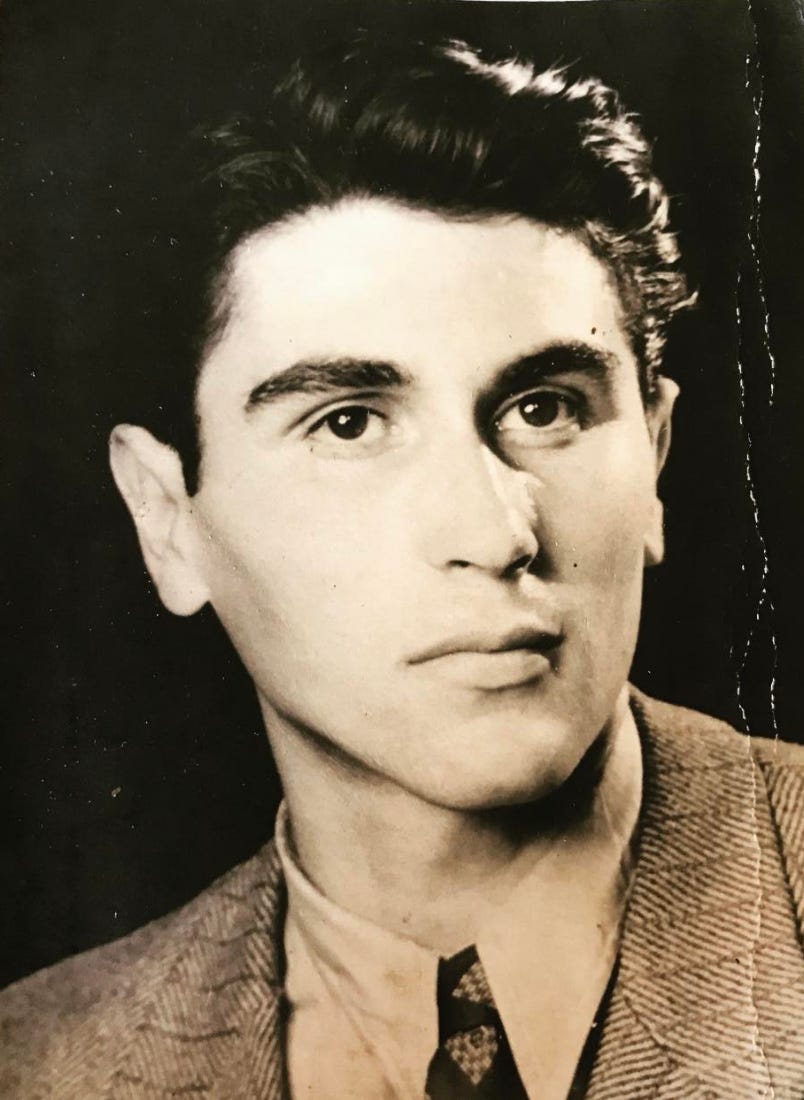

My grandfather, Janos, constantly reminded us that we were beautiful (and that I should keep my hair out of my eyes, and maybe some time in the sun would help that acne). The way he told you something made you believe it—that was one of his gifts—but I think I believed him about beauty because he had a rare appreciation for beauty in life. War displaced him from his family, his country, his name. Life in America was not easy. Despite this, his life seemed to be about beauty: his wife (his English rose), his children, his writing, art by friends and family everywhere, the birds he watched from the back deck, the cowboy boots he adopted as a signature look.

Janos was unabashedly vain. When a war wound required reconstruction of one of his ears, the other was pinned back to create a sense of symmetry; finally, his one source of insecurity, his protruding ears, were fixed. Years later, he even offered to pay for my father’s ears to be pinned (though with what money, none of us could say). He only stopped smoking a pipe after getting veneers; health be damned, white sparkling teeth, however… But we loved his vanity. He absolutely cared what he looked like, and my grandmother kept him clothed in the wide-collared peasant shirts and loose leather vests that completed his bohemian, farmer-writer look. Even as he shrank from 6’ 2” to my height (5’ 11”) in old age, he was a beautiful, impressive man. People wanted to be near him. He was magnetic. And so, in the sense that he was someone or something that you don’t wish to be without2, he was among the most beautiful people in the world.

His beauty, his belief in his beauty, his belief in my beauty, made me believe in me. That old cliche, “beauty comes from the inside,” has some merit in the sense that to know oneself brings confidence, and that confidence is alluring. In her essay, “Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self,” Alice Walker details how a childhood accident that left her with a blind, cloudy eye, changed her from an outgoing, confident little girl to an anxious, withdrawn young woman. It’s not necessarily that she is teased about the eye, as that she immediately feels that she is not the beauty she once was. The eye is a defect, until decades later when her young daughter sees the cloudy eye as a planet, the earth from space. Then, the eye is no longer shameful. Walker can remember what it is to feel beautiful. The internal and external are connected—not in the classical sense of beautiful bodies indicating good souls, warty skin as marred by evil—but as an understanding of how we inhabit our worlds. If we feel we are a spectacle, at the mercy of the eyes of others, we shrink and crouch. If we don’t worry about the eyes of others, that very confidence draws attention; but the attention is no longer needed.

Walker’s reimagining is a form of body positivity—changing the narrative about something so that it can be embraced. In her essay, we understand both the shame that traps her, and how changing the story of the eye changes her narrative. Words do have the ability to affect what something means, and we frequently inflect our understandings of our worlds and selves through our narrative perspective, whether intentionally or not.

Unfortunately, words written without conviction are meaningless. Body positivity, or at least its current populist form, doesn’t quite work for me because it doesn’t seem to properly examine the underlying feelings about the body. Our relationships to our bodies are very rarely, if ever, our own; rather, they are refractions of a million cultural messages we’ve absorbed since long before we could question the meaning or history of such ideas. Every day, I learn something new about the Western or American or Southern or Shermyen approach to the body. Every day, I realize where a preference or dislike comes from, how malicious or just plain random a rule on beauty is. Popular iterations of the body positive movement frequently use language similar to that found in toxic positivity, a relentlessly positive approach to life that seems to put you in the position of feeling shame for any negative emotions, rather than accepting that not every lemon becomes lemonade. Sometimes the lemon is rotten. Sometimes it’s just yellow shit.

But I’m not sold on body neutrality, either. Maybe it’s the name that doesn’t work for me, or the common ways I’ve seen it deployed online are misunderstandings, but complete neutrality has a utilitarian bent of which I am wary. Not because I fear body neutrality could be ableist (though certainly some conversations about valuing a body for what it does for you can enter dicey territory), but because I dislike anything that sees the possibility of beauty as frivolous, as icing, rather than the cake itself.

I can see the value of that neutrality as a way to re-enforce appearance as amoral, divorced from a long history of visual appearance (or other sensory details—body odor, tone of voice) as indicator of internal worth. There’s a reason the witches are ugly, the princesses fair. As my body changes, I wouldn’t have to deal with the pain of losing a form of beauty in myself: like the idea that my beauty is an undeniable fact, I’ve also known that my hair would age early. I began finding grays when I was sixteen, and determined then that I would not dye my hair. Gray hair was easy to accept—there’s been a larger cultural push to embrace gray. I could be a silver fox. What I know will be more difficult is lines on my face. Gray hair is genetic; wrinkles and uneven skin tone are associated with smoking, sun damage, a hard life. There’s more work involved in unlearning the symbolism of aging, the harsh names like “crow’s feet” or “liver spots.” Unfortunately, I’ve tried being divorced from my body, a brain in a jar, and it never works. Maybe I’m not doing it right, but the approach makes me feel awkward and clumsy in my skin suit, ungrounded, alien.

I agree that I don’t see the stretch marks on my hips or the keratosis pilaris on my legs as tiger stripes or whatever brave-yet-femme-coded thing small angry red bumps could be (plucked chicken dots? I’m bad at this). I don’t see them as beautiful, and forcing myself to see them as beautiful is unhelpful—there is no organic epiphany here, like that experienced over Walker’s cloudy eye. But I don’t want to be neutral about the rest of myself. My job is to read and think about life and culture through literature, and for me, it is the pleasure I find in the author’s word choice, the sound or rhythm of a line, that largely separates my work from that of a historian. Why would I ignore something that could bring me even a second’s pleasure? Life is hard enough.

I should take a minute here to define beauty.

I can’t, really. But here goes.

Beauty is vague and massive and at some point I’ll properly delve into the history of the term. But for now, you should know that my definition of beauty is simple: sensory pleasure. While I believe beauty to be good, the beauty of an object or being does not affect its inherent goodness—beauty has no relationship to morality. Beauty is less, as Umberto Eco writes, “a reaction of disinterested appreciation” than it once was3. Rather, modern descriptions of beauty as breathtaking or arresting have more in common with what he describes in defining ugliness: “synonyms for ugly contain a reaction of disgust, if not of violent repulsion, horror, or fear.” What is beautiful and what is ugly are not the same, of course, and repulsion differs from desire. But the reactions to both are now active--beauty AND ugliness incite. Modern ideals have more in common with what Burke might have called “sublime,” a term which he associates with lofty, haughty, not docile enough. Basically, beauty is a term that morphs in relation to cultural moments. It is not static, and there’s no reason you can’t find your own definition. Though you’re welcome to borrow mine.

My wariness of neutrality comes also from the the relationship between pleasure and beauty. If my partner finds pleasure in my beauty, then I want to as well. Why should he get the most out of my appearance when it is mine? Maybe my desire to embrace vanity comes from knowing that there will be people out there taking pleasure in my appearance (sexual sometimes, perhaps, but more likely the same pleasure I provided at those tea parties, the pleasure of a vista, a sight, that I too find in the faces of strangers) and that my appearance should serve me most of all. Not through the machinations of capitalism, by which my body and face are held up to financial valuation. I mean in the simplest way: if I see my face, if I hold up the mirror, why should I not get a thrill?

Vanity gets a bad name for the same reasons that beauty gets a bad name: we assume that you like looking at yourself because it reminds you of your place and power in a terrible system. And we tend to not like people reveling in the power of beauty because we tend to call female-identified people beautiful, and for many years, beauty was explicitly defined as not simply pleasing to the eye but also docile, submissive. If you know the power of your beauty, why would you remain submissive and docile?

You might argue, “Sarah, it’s easy for you to find yourself beautiful because you’ve told us that the world re-enforces that opinion.” You’re right. I might not line up to every single American beauty ideal, but I’m certainly not the target of cruel remarks about my appearance, at least, not for many years now. It is easier to hold a belief as true when those around you support it as such.

But it’s this whole system that I want to exit in my fight for vanity. In the 1970s, a number of prominent feminist critics argued that we’d pretty well-established the masculine bent in everything, including our language. Women are defined by their otherness to man,4 everything is dichotomous, binary, oppositional, and the only way to truly exit the system is to tear it down and rebuild it completely. The name for the idea of this language or communication (as yet, we haven’t figured out how to create it) has been “feminist poetics.” I mention feminist poetics because I think we have a similar issue with beauty. When I ask my students to define beauty, the most common answer is some variation on “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Do you see the problem?

Feminist poetics is an attempt to escape from womanhood defined by men. My embrace of vanity is an attempt to escape from beauty defined by my beholder. The problem of letting the beholder decide is that those eyes have been swayed through years of conscious and unconscious conditioning. Sometimes it might work in my favor, sometimes it might not. But why should what brings pleasure to another be what has to bring pleasure to me?

My “body poetics,” like feminist poetics, is purely theoretical at the moment. There’s rarely a good way to start from scratch. But here’s what I propose in the meantime, to let you worry only about your own gaze, without feeling as if you are lying to yourself.

What you see as beautiful does not need to be in competition with other sorts of beauty. As art styles have proliferated, we haven’t felt the need to rank impressionism vs expressionism vs pop art vs post-impressionism vs figurative painting and on and on. Likewise, when I admire the squareness of my jawline, I do not hold up my jawline as the best of all possible jawlines. I enjoy the look of soft and rounded, pointed to a chin, stubbled. My hazel eyes don’t need to be better than my father’s hazel eyes or my brother’s brown ones or my mother’s green ones. I admire my curls, a pin-straight bob, a shaved head. I admire curls looser than mine, tighter than mine, neater than mine, messier than mine. I admire my me-ness. I bring joy to myself. Umberto Eco speaks of classical Greek definitions of beauty with the terms “harmony” and “proportion” in his History of Beauty. At first glance, this seems to support the idea of perfection, but I think it is modern interpretation that holds perfect beauty as an unattainable, Platonic ideal. Why shouldn’t “harmony” and “proportion” simply refer to a mean, an average? A statistical fact?

I think we know that not all in the world is beautiful—that’s why Dove ads empower no one. They simply make “beautiful” meaningless, or force us to say, “everyone may be beautiful, but she is more/less beautiful than me.” The Dove ads fail because they’ve given us no real way to combat the old system, to ask why we’re so damn hard on ourselves, why acne or fat distribution or skin tone make us feel shame and hatred. Here’s the thing: I can dislike those stretch marks and that chicken skin and the acne I get each month without hating myself, or having to feel as if I have no relationship with my body. I can love a partner, my parents, my dog; that doesn’t mean there aren’t things I find frustrating about each of them. But those small frustrations don’t make them unbeautiful. I don’t have to be zen and neutral; when I become frustrated by something that someone I love does, I take a breath and ask myself why? When I become frustrated with myself, again, I do not shove the feeling aside, but ask why—why do I feel guilty about an ungraded stack of papers? When I hate my acne, I ask why? And I remember: the dermatologist who said washing your skin would always prevent acne (obviously untrue, and made me feel dirty), hearing that acne was an affliction of teens (ha!), the million targeted ads that mean I’m never not thinking about some new gadget or system for clearing tiny sebum plugs from my skin. And if I think about all of that, I don’t love my mild acne. But it suddenly seems rather exhausting to devote so much angst to it. And I won’t let a goddamn break-out negate my ability to find beauty or joy in myself. As the definition of the term beauty is not static, we can indulge in not being static in our approach to self.

Finally, while I don’t think we should be engaging in out and out narcissism, or total self-obsession, what’s wrong in finding ourselves attractive? Stimulating? Divorcing sexual attraction from human beauty is not always useful. Should we stop sexualizing girls? Yes. Obviously. Should people not yell obscene phrases at women on the street? Also yes. But the big issue here is not so much sex and attraction, but the beholder controlling the narrative of the beheld. Expanding ideas of beauty helps both the admired and the admirer--just as I wish not to be objectified, I would prefer to be a lover than a fetishist. Attempts to divorce sex and sexual attraction from beauty are simply vestiges of a puritanical approach to aesthetics.5 Elaine Scarry writes that “Beauty brings copies of itself into being:” this applies not only to the human desire to make art, but also to the basic desire to reproduce6. Essentially, when you see a body that you love, you wish to make copies of it—this could also apply to the self (having children is a desire to see some of yourself in another, at least at some level). In queer couplings, this clear reproductive intent is fuzzier, but surely the desire to be near the beautiful, and by extension pleasure, is reason enough to keep sex and beauty in the same conversation. What do we gain from separating the ideas of attraction and beauty? Beauty without magnetism brings us back to pseudo-scientific arguments about perfect facial proportions; that’s a beauty that is boring, sterile, and ultimately harmful.

Beauty is political. It is cultural. Beauty as an aesthetic category helps us understand gender as a social and political phenomenon. We can’t exit it, we can’t dismiss it, so we must learn to live with it. Perhaps you can be neutral, but I can not—so I’ve decided to be beautiful. But not for you. My pleasure in my appearance comes first, and I will get more out of it than anyone else.

I am Vanity. Bring me my hand mirror.

I started writing this essay a couple of weeks ago, before Emily Ratajkowski started posting sections from Berger’s text in her insta stories, including this exact quote. Absolutely loved seeing this, as I teach this text in my “On Beauty” version of ENGL 1102.

I’m borrowing here from Elaine Scarry. Her book On Beauty and Being Just is what I’d recommend, with Berger, as the introduction to considering your own relationship to beauty. “It is not that beauty is life-threatening (though this attribute has sometimes been assigned it), but instead that it is life-affirming, life-giving; and therefore if, through your careless approach, you become cut off from it, you will feel its removal as a retraction of your own life” (27).

Umberto Eco, On Ugliness. This and his History of Beauty are great coffee table books to introduce you to the artistic renderings of these ideas, ugliness and beauty, in the West.

In Freud, women are explicitly defined by lack, that we inspire men with castration fear—if you didn’t already dislike Freud, maybe you will now.

After reading Whitney Davis’s Queer Beauty, I wonder if these attempts also come from homophobia—she clarifies some of the male Victorian anxieties of expressing aesthetic appreciation as merely homosocial—and that sexual attraction is not really the complicating force we make it out to be.

from On Beauty and Being Just